Misunderstanding South Africa’s Foreign Economic Relations and Worker Productivity

South Africa’s class struggle generated two gold medals for performance in 2014. In February, PricewaterhouseCoopers identified the Johannesburg bourgeoisie as, according to The Times, “the world leader in money-laundering, bribery and corruption, procurement fraud, asset misappropriation, and cybercrime,” with 77% of all internal fraud committed by senior and middle management. (This may help explain SA’s 2013 rating as, according to the International Monetary Fund, the third most profitable country for corporations among major economies.)

Then in September, for the third year in a row, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report ranked the South African proletariat as the world’s most militant out of 144 countries surveyed. The intensity of South Africa’s class struggle is reflected in the war of ideas just as much as in the strike wave that commenced in 2012.

South Africa’s leading corporate-funded strategic think-tank is the Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE). Last week’s input to CDE by Harvard Center for International Development director Ricardo Hausmann—“Raising South Africa’s ‘speed limit’”—makes two central claims about, first, the current account and, second, the allegedly high cost and low productivity of labour.

As a third complaint, Hausmann cites an immigration policy hostile towards skilled workers, a minor matter about which CDE campaigns regularly, and about which I do agree. Having immigrated to South Africa in 1990, my own ideological bias can be summed up in a slogan, “for the globalisation of people and the deglobalisation of capital.”

This is the same bias expressed once by John Maynard Keynes: “Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national.”

Current account conflicts

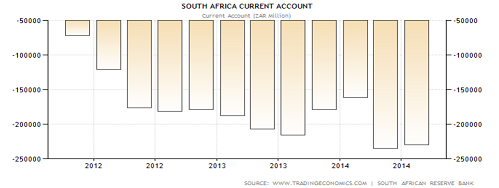

Mainly because South African finance has not stayed within national boundaries, especially after exchange controls were partially lifted in 1995. Most of the largest firms listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange emigrated five years later. And, partly because since trade liberalisation began in earnest in 1994 we have not been buying homespun goods, the result is one of the world’s highest current-account deficits.

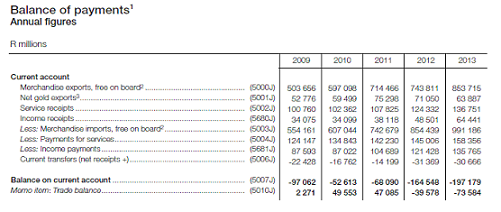

To cover payments on that deficit, soaring international borrowing signals what may become a sovereign debt crisis (moderate local, rand-denominated state borrowings and tokenistic social spending ratios put South Africa at the low end of the emerging-markets peer group). The foreign debt has risen from $25 billion in 1994 to $140 billion today; since 2006, the foreign debt/GDP ratio more than doubled from 18% in 2006 to the present danger zone of 38%, not far off the mid-1985 crisis level at which point the apartheid president, P.W. Botha, had no option but to default.

What’s the root cause? Hausmann traces the rising current-account deficit solely to our failure to trade harder with foreign partners: “When my colleagues and I started advising the South African government in 2004 we emphasised the importance of increasing exports to create more jobs and to fund the current account deficit. With the current lack of export dynamism South Africa is not going anywhere.”

He continues, “The rand [the SA currency] has weakened significantly, which should favour exports over imports, but we have not seen this affect the export numbers. Export jobs are hard to create because they need to compete with other exporters in other parts of the world. But there is no way around this. Exports, and jobs related to exports, are the key to growth.”

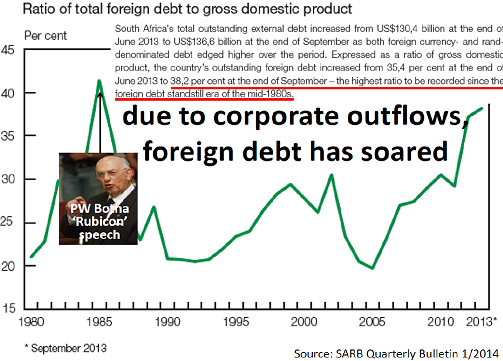

Hausmann’s emphasis on the trade balance as the core of the current-account crisis is misplaced. Over the last five years for which there is full data, from 2009-13, South Africa suffered a nominal aggregate trade deficit of R14 billion ($1.2 billion). In contrast, the nominal net outflow of profits, dividends and interest was R315 billion ($27.4 billion).

In other words, it’s not insufficient trade but financial hemmorhaging that creates the crisis. Both licit and illicit outflows of capital from South Africa are so serious that they reached as high as 23% of GDP in the peak year of 2007, according to Wits University economist Seeraj Mohamed.

The problem for Hausmann and the CDE is that if the genuine cause of the current-account deficit is even mentioned, much less recognised honestly, the next logical question arises: how do we stop the outflow of profits, dividends and interest?

There are two logical answers of which Keynes would approve. First, halt illicit capital flight, in part by regulating companies like fib-prone Lonmin—of Marikana Massacre fame—whose Bermuda “marketing” arm is suspiciously costly, according to the Alternative Information and Development Centre (AIDC); or De Beers, a major CDE donor which misinvoiced $2.83 billion of South African diamond deals from 2005-12, according to my colleagues Khadija Sharife and Sarah Bracking.

In 2011, Sharife’s “Rough and Polished” critique reveals, although 12% of world diamond production—worth $1.73 billion—came from South Africa, the royalty accrual was just $11 million: “Companies here pay a royalty rate far lower than that of other African states. Companies can also reduce or cancel out export taxes if they offer locally-mined diamonds to the state for purchase—even if the South African government never buys the gems, often due to formidably high prices. In an apparent conflict of interest, De Beers ‘donates’ paid staff to the State Diamond Trader, charged with assessing diamonds offered by De Beers and other companies to the state for purchase.”

Would CDE director Ann Bernstein care to publicly debate the current account deficit, using De Beers as a case study? That is, as a study dedicated not to showing “the most dramatic example of a large multinational transforming the economic fortunes of a southern African country” (Botswana), as she has claimed of De Beers, but instead to considering the mining house’s alleged tax avoidance?

The second obvious solution is capital controls, also known as exchange controls, upon which, said Keynes, “In my view the whole management of the domestic economy depends.” This is still correct, 80 years later, and in a new report by University of Massachusetts scholars James Boyce and Léonce Ndikumana, various “Strategies for Addressing Capital Flight”—including non-corrupting exchange controls—are reviewed.

Frankly, given how uncomfortable this research is for Hausmann and the CDE, I don’t expect them to be honest enough to read the studies by the AIDC, Mohamed, Sharife-Bracking, or Boyce-Ndikumana (never cited by the CDE or its consultants), much less openly grapple with these challenges.

Yet once the forces behind the current-account deficit are better known and the solutions debated, perhaps South African society can stand up to immoral financiers and tax-dodgers—as was accomplished in getting access to AIDS medicines a decade ago and ending corporate-supported apartheid two decades ago?

Hausmann and the World Bank join South Africa’s class struggle

Hausmann has joined South Africa’s class struggle in full throat. A Venezuelan economist who is also a World Bank consultant, he receives regular invitations to speak soothingly about “economics of inclusion” from banks like JPMorgan, Citi, and Union Bank of Switzerland. Hausmann was hired by former South Africa President Thabo Mbeki as his highest-profile international economic advisor from 2004-08 (ironically Mbeki’s last major speech as president, in September 2008, was when hosting Hugo Chavez).

But he has a curious reputation. Hausmann was Venezuela’s planning minister in 1992-93, during the corrupt, neoliberal, and brutal reign of Carlos Andrés Pérez, and does not hide his dislike for the current democratic government, first elected in 1998. That bias emerged on at least two occasions:

- in 2004, when Hausmann charged there was electronic voting fraud in a recall referendum (a claim rejected by other researchers as well as by the Jimmy Carter Center, which is perhaps the world’s leading NGO authority on elections); and

- a decade later, when Hausmann and a co-author incorrectly claimed that Venezuela’s president Nicolás Maduro was about to default on the foreign debt, thus spiking Venezuelan interest rates upwards.

As explained at VenezuelaAnalaysis by a South African writer active in Boston solidarity efforts, Suren Moodliar, “If there are any doubts as to Hausmann’s concerns for the poor, we must ask where those rested when he was in power and implementing a harsh austerity program. Hausmann’s own values are hinted at when he castigates Nicolás Maduro by calling the president a ‘tropical thug.’ One can and should denounce thuggish behaviour, but his adding the adjective ‘tropical’ casts things in a different light. Those of us from the Global South or familiar with ruling-class racism readily recognize what is intended by the word.”

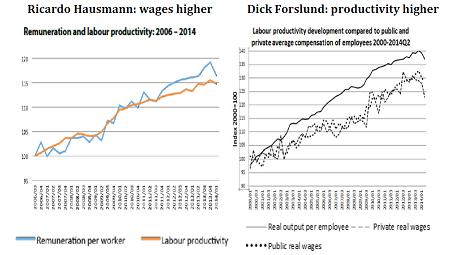

Ruling-class classism is just as pronounced. By distorting the data, Hausmann claims that in South Africa, “the rate at which remuneration has been increasing is far above the rate at which productivity has been increasing.”

It is true that because of the mass strike wave since 2012, there has been a recent decline in labour productivity (as one would expect since so much production was stalled). But to dramatise his critique of workers for the CDE, Hausmann starts his index at a curious point: the third quarter of 2006.

In contrast, economist Dick Forslund of the Alternative Information and Development Centre in Cape Town provides a 2000-14 graph based upon the South Africa Reserve Bank’s Quarterly Employment Statistics. It provides much better context, showing how productivity outstripped wages from 2002-11.

In 2012, Forslund had chided a CDE booklet for claiming there were labour productivity declines of 2.5% per year in the 2000s. CDE arrived at this bizarre result, Forslund argued, by “using two statistical tables in which historical underreporting from employers completely distorts the numbers.”

In reality, though, said Forslund, “Labour productivity has increased at an average rate of about 3%, quarter by quarter in 12 month periods, during the last ten years. Real wages have increased at an average yearly rate of only a little more than 2% during the same period or at a 0.9 percentage points lower rate.” As a result, “the wage share of the national income has been falling since 1998. The profit share of the national income rises correspondingly.”

Like its consultant Hausmann, the World Bank was recently caught using extremely dubious data to claim that world-leading South African inequality, measured as the Gini Coefficient from 0 (least unequal) to 1 (most unequal), needs recalculation to account for “fiscal tools” of taxation and state spending. The Bank claims that the Gini plunges from 0.771 to 0.596 once these are considered.

Except that the Bank refuses to calculate South African state subsidies to corporations, so the claim is utter nonsense. (Bank bias becomes especially obvious when the report is enthusiastically endorsed by local neoliberals intent on budget cuts, even though staff say that is not their intention.)

In an email to me on Monday, December 8, chief World Bank economist for Africa Francisco Ferreira dismissed concerns about his colleagues’ Gini Coefficient data manipulation. I specifically asked about the decision to ignore corporate subsidies when calculating the allegedly “comprehensive” impact of fiscal policy on inequality, and he answered: “It is certainly possible that reasonable people might disagree about specific methodological decisions taken. That said, the approach taken [by the Bank’s Pretoria staff] strikes me personally as carefully thought out, theoretically sound, and well implemented.”

There you have it: an unabashed reconfirmation of the Bank’s pro-corporate bias and an endorsement of “theoretically sound” white-washing of the worst inequality of any major country in the world. My request to the Bank for a public debate? Ignored.

South Africa’s economic crisis is worsening. And the extreme outflows in the current account, the declining ratio of wages to profits notwithstanding the intense strikes, and the country’s extraordinary inequality together explain why one team is clearly winning the epic class struggle here: capital.

But that doesn’t mean capital’s ideas have merit; they really don’t, as you see after even a rudimentary class analysis.

Patrick Bond directs the University of KwaZulu-Natal Centre for Civil Society in Durban.

Triple Crisis welcomes your comments. Please share your thoughts below.